1. How housing affects health

Where someone lives—both in terms of the stability, affordability, and quality of housing, and the characteristics of their neighborhood—can have a profound impact on their health and wellbeing.

A lack of affordable housing options can limit a person’s ability to maintain stable housing and access other services, including staying engaged in ongoing health care. [4] An overall inadequate supply of affordable housing in the United States, paired with regulations that discourage the development of new housing, creates barriers to maintaining stable housing for many.

Over the last five years, the average rent in the United States has increased 18%. [5] Job and income losses related to the COVID-19 pandemic have increased challenges with housing affordability for millions of households, especially lower-income households and households of color. [5] In 2020, 30% of households across the country were cost-burdened, meaning they were paying more than 30% of their incomes on housing. [6] Fourteen percent of households were severely cost-burdened, paying more than 50% of their incomes on housing. [6] The increase in unaffordable housing is linked to increasing rates of housing instability and homelessness. Some populations, especially Black/African American (hereafter referred to as Black), Hispanic/Latino, and other communities of color, as well as transgender communities, also face housing-related discrimination, further limiting their access to stable housing. [7], [8]

Stable housing is closely linked to successful HIV-related health outcomes. People experiencing homelessness or housing instability have higher rates of HIV and mental health disorders than people with stable housing. [14], [15] People experiencing homelessness or housing instability are also more likely to engage in activities associated with increased chances of HIV acquisition or transmission, including substance use, injection drug use, and having multiple sex partners—factors that can also contribute to higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and hepatitis. [16], [17], [18], [19] People with HIV also experience greater risk for inadequate care and treatment due to unstable housing and housing loss. [4] According to CDC data, in 2020, 17% of people with diagnosed HIV experienced homelessness or other forms of unstable housing. [20]

2. What the data tell us

Research shows that housing instability is a significant barrier to HIV care and is associated with higher rates of behaviors that may increase the chance of getting or transmitting HIV, such as substance use and condomless sex. [4], [15], [16], [21] People with HIV experiencing homelessness are also more likely to delay entering HIV care, have reduced access to regular HIV care, and poorer adherence to antiretroviral treatment. [16]

HIV testing: Data show that people experiencing homelessness or housing instability are less likely to report having tested for HIV in the past year [22] or ever, [23] compared to people with stable housing. One study found that gay and bisexual men experiencing homelessness are over 15 times more likely to delay HIV testing than those with stable housing. [24] Having access to general medical services is associated with higher likelihood of HIV testing, [25] and recent access to any medical or dental services increases the likelihood of HIV testing among people experiencing homelessness. [26] Meeting people where they are with the services they need can help overcome barriers posed by unstable housing and homelessness and support people to access and stay engaged in care.

PrEP use: People with unstable housing face barriers to accessing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99% when taken as prescribed. [27], [28], [29] One study found that knowledge of PrEP was low among youth experiencing homelessness, especially in the U.S. Midwest and South; only 29% had any knowledge of PrEP and only 4% had talked with a provider about PrEP. [30]

HIV treatment: People experiencing homelessness are less likely to receive and adhere to antiretroviral therapy (ART), compared with people who have stable housing. [16], [31] In one study, Black gay and bisexual men who self-reported homelessness were more likely to report difficulty taking ART and of missing a dose in the past week, compared to those with stable housing. [32] Another study found that homelessness can affect ART adherence among people with HIV who inject drugs due to multiple factors, including lacking a place to store the medication and lack of privacy. [33]

Viral suppression: Taking HIV medication as prescribed can help people with HIV stay healthy, and get and stay virally suppressed, or have an undetectable amount of HIV in their blood, which means they will not transmit HIV to their sex partners. Research shows that housing instability and homelessness can create barriers to becoming and staying virally suppressed. [17], [34] Transitioning to more stable housing can help people stay engaged in HIV care and get and stay virally suppressed. [35]

Key terms

Housing instability: an umbrella term that encompasses homelessness and other housing-related challenges people may experience, including affordability, safety, quality, overcrowding, moving frequently, living in transitional housing or extended stay hotels, couch surfing, eviction, loss of housing, or spending a bulk of household income on housing [9], [10], [11]

Homelessness: lacking a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, such as living in emergency shelters, transitional housing, or places not meant for habitation (e.g., on the street, in a car); or an individual or family who will imminently lose their primary nighttime residence (within 14 days) and has not identified subsequent housing; or unaccompanied youth younger than 25 years of age, or families with children who qualify under other federal statutes, who have not rented or owned housing in the last 60 days, have moved two or more times in the last 60 days, or who are likely to continue to be unstably housed because of disability or multiple barriers to employment; or an individual or family fleeing or attempting to flee domestic violence, has no other residence, and lacks the resources or support networks to obtain other permanent housing. [12]

Cost burdened: households are considered cost burdened if they spend more than 30% of their income on housing and severely cost burdened if they spend more than 50% of their income on housing [13]

Ending the HIV epidemic in the United States requires implementing integrated solutions that address the comprehensive health, social services, and housing needs of people with HIV and people who could benefit from HIV prevention so they can stay healthy and prevent HIV acquisition or transmission. CDC is actively working with other federal agencies, people with HIV, and other community leaders to implement strategies that increase access to affordable, high-quality housing and support national HIV prevention goals.

Some populations are disproportionately affected by both housing instability and HIV, highlighting persistent disparities in access to critical health and social services by race, ethnicity, age, and gender identity.

Black people make up over 40% of the population experiencing homelessness in the United States, [36] and 42% of new HIV diagnoses, [37] despite making up only 14% of the population. [38] Due to historical racial discrimination and residential segregation, some Black people live in communities with the highest social vulnerability, in which a number of factors, including poverty, lack of transportation access, and crowded housing, increase vulnerability to negative health outcomes and make it harder to obtain HIV care services. Black adults who live in communities with high social vulnerability have increased chances of receiving an HIV diagnosis compared with Black adults in communities with the lowest social vulnerability. [39], [40] In 2019, 11% of Black people with HIV reported homelessness in the past year. [21]

Hispanic/Latino people make up just over 22% of the population experiencing homelessness in the United States, [36] and 27% of new HIV diagnoses, [37] despite making up only 19% of the population. [41] Data show that over 8% of Hispanic/Latino people experience homelessness at some point during their lives. [42] In 2020, 8% of Hispanic/Latino people with HIV reported homelessness in the past year. [21]

Young people with unstable housing experience up to 12 times greater risk of HIV infection than those with stable housing, [43], [44] and young people with HIV experience higher rates of homelessness than do people with HIV in other age groups. In 2019, youth (ages 13-24) and younger adults (ages 25-34) made up 57% of new HIV diagnoses, [45] and 14% of people ages 18-24 and 16% of people ages 25-34 reported homelessness in the past year. [21] While youth experiencing housing instability or homelessness have overall high rates of HIV testing (attributable in part to availability of HIV services at youth drop-in centers), [46], [47] research suggests that this population faces increased barriers to HIV prevention education and PrEP uptake, including perceived lack of risk and concerns about medication side effects and cost. [48]

Transgender and gender non-conforming people are more likely to experience housing instability or homelessness than cisgender people. [49] From 2016 to 2019, the number of adult transgender people experiencing homelessness in the United States increased 88%. [49] One analysis of studies conducted between 2006 and 2017 found that 30% of transgender people reported unstable housing or homelessness. [50] Transgender people are also affected by HIV: in 2019, transgender people accounted for 2% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States and dependent areas, and HIV diagnoses among transgender people increased 7% between 2015 and 2019. [45] Transgender women are disproportionately affected by HIV, with prevalence estimated at 14%. [50]

Structural interventions that address housing and HIV-related health needs in an integrated, comprehensive way can improve health outcomes for people with HIV and people who could benefit from HIV prevention. [51] Among people without HIV, long-term supportive housing for people who need it can decrease the risk of getting HIV. [52] For people with HIV, rental assistance programs can help increase access to stable housing, and support improved health outcomes for those experiencing homelessness and housing instability. [53]

Studies have shown that meeting people experiencing housing instability where they are with needed services can help improve HIV-related health outcomes. For example, one study found that rapid HIV testing outside of traditional care settings, such as homeless shelters, increased testing uptake among people experiencing homelessness or housing instability. [22] Accessible and flexible PrEP navigation services tailored to clients’ needs, including street-based outreach, have also been shown effective in achieving PrEP initiation and adherence among people who use drugs and are experiencing homelessness that are comparable to rates among other populations. [54]

Some studies have demonstrated that housing-focused interventions, such as those that provide rental assistance, permanent supportive housing, case management, and follow-up services, can be cost-effective strategies for HIV prevention. [55], [56] One study found that preventing only one HIV transmission for every 64 clients would make such interventions cost-effective. [57]

3. How federal agencies are addressing housing and HIV

The National HIV/AIDS Strategy for 2022-2025 calls for a whole-of-society national response to accelerate efforts to end the HIV epidemic in the United States by 2030 and support people with and affected by HIV with the services they need to be healthy. The national strategy specifically calls for approaches that address housing and other social determinants of health alongside other co-occurring conditions that impede access to HIV services and exacerbate HIV-related disparities. [58] A federal implementation plan released in August 2022 outlines how collaborations within and across federal agencies can advance strategy goals and improve quality of life and health outcomes for people affected by HIV.

The federal Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. (EHE) initiative, launched by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 2019, also supports innovative, community-driven solutions to help people access the HIV, healthcare, and social services they need to stay healthy. Through cross-agency collaboration, the initiative seeks to improve service coordination and eliminate social and structural barriers to prevention and care.

CDC

Programs across CDC recognize the importance of addressing social determinants of health, including housing, to improve health outcomes. As part of its overarching goal to advance health equity, CDC is collaborating internally and externally with diverse partners to identify best practices for addressing housing and HIV.

CDC is charged with the mission of preventing HIV and improving HIV-related health outcomes, including by addressing social determinants of health. CDC’s activities to address housing and HIV include:

Cross-CDC collaborations: Across CDC, programs and health equity leaders collaborate to share data and develop, assess, and implement interventions that address social and structural determinants of health, including housing, in line with CDC’s priorities for reducing sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (Strategic Plan 2022-2026 and Community Approaches to Reducing Sexually Transmitted Diseases initiative).

Community engagement: Meaningfully engaging with communities and partners is a vital part of CDC’s process to develop programs and activities that address barriers to HIV and other health and social services. CDC prioritizes hearing from and collaborating with people with HIV through ongoing community listening sessions and building partnerships with organizations and other federal agencies focused on issues that intersect with HIV and affect health outcomes, including housing. CDC has hosted roundtables with regional leaders and town halls with community members to gain community insight into local HIV and housing efforts and how CDC can support those initiatives.

Program implementation: CDC supports state and local health departments and community-based organizations to implement evidence-based, high-impact programs to improve access to HIV and other health and social services. Through EHE, CDC funds 32 state and local health departments to implement locally tailored and integrated solutions to meet the unique needs of their communities. This funding also provides flexibilities for health departments to use funds to support housing. CDC also funds over 100 community-based organizations and their clinical partners to deliver comprehensive HIV services to communities disproportionately affected by HIV. CDC also supports the Housing Learning Collaborative, a virtual learning community to build capacity of EHE jurisdictions to develop and implement innovative programs to respond to housing-related needs. CDC’s HIV Strategic Plan Supplement for 2022-2025 includes a focus on status neutral and whole-person approaches to HIV prevention and care that address social and structural barriers that deter people from seeking the care they need.

HIV surveillance data: CDC’s National HIV Surveillance System is the primary source for monitoring HIV trends in the United States. CDC funds and assists state and local health departments to collect the information and report de-identified data to CDC for analysis and dissemination. Based on this information, CDC can direct HIV prevention funding to communities where it is needed most. Additionally, the Medical Monitoring Project, led by state, local, and territorial health departments in partnership with CDC, collects data on HIV care engagement and barriers to care, including housing instability and homelessness, among people with diagnosed HIV to help determine the health and social services people need to stay engaged in care.

Research: CDC conducts research and demonstration projects to build the evidence base for effective HIV prevention interventions. The Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions and Best Practices for HIV Prevention includes several housing-focused HIV prevention and care interventions. These include the Enhanced Housing Placement Assistance program for people with HIV experiencing homelessness; the Shelter Plus Care program in Ohio, which is regulated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and provides rental assistance and supportive services to people with HIV experiencing homelessness and their families; and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Homeless Initiative, which provides patient navigation services to people with HIV experiencing homelessness or housing instability.

HUD

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) recognizes quality, affordability, stability, and location of a home are important factors for health and well-being. HUD administers a variety of housing assistance programs with a broad reach and ability to assist people with HIV, very low-income families, the elderly and aging, persons with disabilities, and others in need of housing assistance.

HUD’s Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS (HOPWA) program is the only federal program dedicated to housing for people with HIV. HOPWA was established by the AIDS Housing Opportunity Act to address the housing needs of individuals with HIV and low incomes and their families. Through HOPWA, HUD’s Office of HIV/AIDS Housing awards grants to local communities, states, and nonprofit organizations to provide rental housing assistance and supportive services for over 100,000 people with HIV and their families annually. HUD provides technical assistance to HOPWA grantees to strengthen their capacity and support communities to develop comprehensive housing strategies. Other HUD programs, including the Housing Choice Voucher, Continuum of Care, and Emergency Solutions Grants programs, also provide safe, stable housing that enables people to prioritize their health and participate in HIV prevention or care services. HUD supports activities and initiatives that expand access to HIV housing and services, reduce stigma, and help people access and remain in medical care. For example:

Cross-agency collaborations: In support of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy federal implementation plan, HUD is working in partnership with CDC to address recent HIV outbreaks in the United States involving people experiencing unstable housing, and the complex and overlapping challenges they face, such as substance use and mental health disorders, injection drug use, food insecurity, and stigma. In October 2022, CDC, HUD, and HRSA presented on HIV outbreak responses at the U.S. Conference on HIV/AIDS (USCHA).

HOPWA funding: On December 1, 2021, HUD awarded over $40 million to 20 communities to implement new projects that align with ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic initiatives and elevate housing as an effective structural intervention in ending the epidemic. Selected applicants received a three-year grant to fund housing assistance and supportive services for low-income people with HIV and their families, coordination and planning activities, and grants management and administration. Additionally, HOPWA funded 143 formula jurisdictions and 82 competitive permanent supportive housing grants in Fiscal Year 2022 with an allocation of $450 million.

Demonstration projects: Since 2016, HUD’s YHDP, Youth Homelessness Demonstration Project has supported communities across the United States to develop and implement a coordinated community approach to prevent youth homelessness. In 2022, CDC and HUD jointly presented a webinar on HUD programs focused on youth populations such as YHDP, Foster Youth to Independence and Family Unification Program can best connect young people to HIV education and services.

Research and knowledge sharing: In 2021, HUD released research on innovative state and local government strategies to remove regulatory barriers to affordable housing and increase housing supply, in order to support inclusive, equitable communities. To promote sharing of knowledge and best practices, HUD’s Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity (FHEO) holds a Table Talks Series to engage HUD grantees and other partners in discussions on fair housing policies.

HRSA

The Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP) serves more than half of all people with diagnosed HIV in the United States, including more than 25,000 people experiencing housing instability. [59] RWHAP helps people with HIV with low incomes receive medical care, medications, and other essential support services to help them stay healthy and engaged in care. HRSA’s Bureau of Primary Health Care (BPHC) supports community health centers to provide primary and preventive care.

HRSA supports innovative interventions, initiatives, and funding models that increase housing access and collaborates with other agencies to promote integration of HIV and housing-related services. For example:

Cross-agency collaborations: CDC is collaborating with other federal agencies, including HRSA and HUD, to cultivate a practice of knowledge sharing and build upon existing efforts to advance health equity and improve HIV-related health outcomes. This includes identifying opportunities for braiding funds and developing inter-agency guidelines on what is allowable; streamlining and harmonizing Notice of Funding Opportunity reporting requirements across CDC and other agencies; and providing guidance and technical assistance to partners and grantees to maximize the effectiveness of housing and HIV-related interventions.

Funding for primary and preventive care: Through BPHC, HRSA’s Primary Care HIV Prevention (PCHP) funding expands access to HIV prevention services, including HIV testing, PrEP, and linkage to HIV care and treatment in EHE-funded jurisdictions. BPHC’s National Health Care for the Homeless Program also supports community-based organizations to provide high-quality, accessible health care, including prevention services, to people experiencing homelessness.

Guidance:In 2016, HRSA issued guidance to RWHAP providers clarifying that Part C funding can support temporary housing services and reducing reporting requirements.

When HUD’s HOPWA program changed how it allocates funding in 2017, HRSA and HUD jointly presented at national conferences to increase understanding of how funding changes could impact RWHAP providers and provided technical assistance on leveraging other funding sources to support people with HIV experiencing housing instability.

In 2017, HRSA and HUD released a joint statement to funded organizations encouraging the sharing of data across systems to better coordinate and integrate medical and housing services for people with HIV. In 2019, the agencies released a toolkit for service providers with best practices for sharing data and improving service coordination

Demonstration projects and research: HRSA’s Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS) program supports the development of innovative models of HIV treatment and care to respond to the emerging needs of RWHAP clients and promote the dissemination and replication of successful interventions. Housing-related SPNS projects include:HRSA’s Homeless Initiative provides patient navigation services for people with HIV experiencing housing instability. A study of the initiative found that people who stabilized their housing were more likely to stay engaged in HIV care, be prescribed ART, and become virally suppressed35

HIV, Housing & Employment Project was launched in 2017 with support from the Minority HIV/AIDS Fund to support the design, implementation, and evaluation of innovative interventions that coordinate HIV care and treatment, housing, and employment services for people with HIV in racial and ethnic minority communities

Addressing HIV Care and Housing Coordination through Data Integration was an initiative to support the electronic integration of housing and HIV care data and improved service delivery coordination between RWHAP and HOPWA

Supporting Replication (SURE) of Housing Interventions was launched in 2022 to evaluate the implementation of housing-related interventions for people with HIV experiencing housing instability and from communities disproportionately affected by HIV, including LGBTQ+ people, youth and young adults (ages 13-24), and people who have been involved with the justice system.

Spotlight on HIV and housing programs in EHE jurisdictions

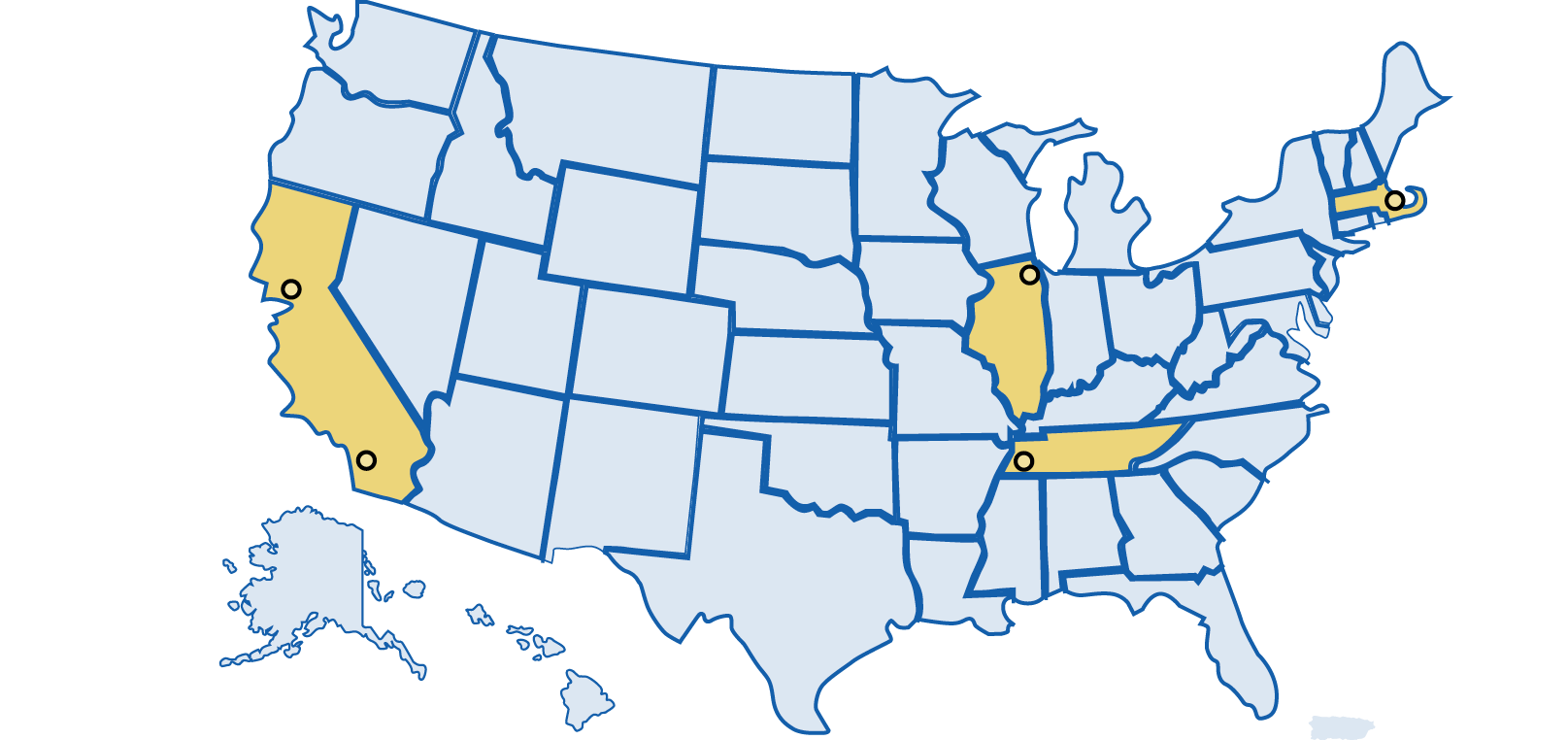

- Riverside, CA: Riverside County’s Housing Authority and local nonprofit TruEvolution launched Project Legacy to provide permanent supportive housing, health care, mental health support services, workforce development, and other wraparound services for LGBTQ+ people and people with HIV experiencing housing instability. [60]

- San Francisco, CA: Through San Francisco’s Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program-funded Ward 86 HIV clinic, the POP-UP Project enrolled clients experiencing homelessness or unstable housing and provided them with low-barrier primary care services, outreach via peer navigator, and integrated social work and case management services. A study of the project found high levels of care engagement among enrollees, despite overlapping challenges of unstable housing, substance use, and mental health conditions. [61]

- Chicago, IL: Chicago House provides housing support, medical case management, and other wraparound services, including linkage to PrEP and mental health services for people experiencing housing instability. Their clients are primarily people with HIV, people who could benefit from HIV prevention, LGBTQ+ and transgender people. Among 41 Housing for PrEP Users clients housed between October 2019 and September 2022, 80% were Black/African American and 20% were Hispanic/Latino; 93% were ages 18 to 35; and 98% identified as gay or bisexual. In addition, over 75% of clients were employed and increased their income while in the program, and 86% of clients who exited the program moved into permanent housing. Notably, 100% of clients remained HIV-negative while in the program. In 2021, 97% of people with HIV in Chicago House residences were linked to and retained in care, and 90% of people with HIV in Chicago House residences were virally suppressed. [62]

- Boston, MA: In response to increasing rates of HIV transmission, Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program launched an innovative PrEP program for people experiencing homeless who inject drugs that provides PrEP navigation services and street-based outreach tailored to client needs, without requiring abstinence from substance use. Of the clients linked to PrEP services, initial data show that 64% were prescribed PrEP and 85% of those prescribed PrEP picked up their prescription. Participants and providers identified program components that facilitated patient engagement, including community-driven PrEP education, accessible programming and same-day prescribing, intensive outreach and navigation, and trusting patient-provider relationships. [54], [63]

- Kansas City, MO: With support from RWHAP and HOPWA, the Kansas City health department launched KC Life 360, a client navigation initiative that coordinates housing and employment services for people with HIV from racial/ethnic minority communities who are experiencing housing instability. The program has improved housing stability and HIV-related health outcomes for participants, with 87% engaging in medical care and 86% becoming or staying virally suppressed. [64], [65]

- Memphis, TN: With support from the Memphis Ryan White Part A Program and Kellogg Health Scholars Program, a partnership was formed between the Shelby County Health Department, Operation Outreach (a federally qualified faith-based health center’s mobile healthcare clinic), and a university to survey and provide voluntary on-site rapid HIV testing services to adults living in transitional housing in the Memphis area. Nearly 90% of survey respondents agreed to test for HIV, suggesting that providing testing services outside of traditional clinical settings is acceptable for this population. [22]

4. The path forward

Continued collaboration with diverse partners can help sustain and advance strategies that consider housing alongside other comprehensive health and social service needs that are critical to ending the HIV epidemic. For instance:

Federal agencies can support inter- and intra-agency collaboration to support policies and programs that address housing and other social determinants of health within holistic HIV programming. For example, they can direct funding and other resources to health departments and other community-based partners implementing integrated services. Federal agencies can also continue to fund and conduct research to build the evidence base for housing-related HIV interventions, and garner support for housing interventions as an effective strategy for improving HIV-related outcomes and reducing long-term health care costs.

Policymakers and elected officials can advance policies that address social determinants of health and increase access to affordable housing, including for people with HIV. They can also invest resources in housing programs for people with HIV, including HOPWA and RWHAP, and invest in other supportive housing efforts for people without HIV who could benefit.

State and local health departments can ensure strong linkages between their infectious disease and housing programs to address housing needs as part of their comprehensive HIV programs. They can direct funding, where possible, toward innovative community-based organization programming that integrates HIV and other health and social services. They can also consider hiring patient navigators to help clients gain access to the services they need to stay healthy, including housing support.

REFERENCES:

[1] CDC. Social determinants of health among adults with diagnosed HIV infection, 2019. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2022;27(No. 2).[2] Stahre M, VanEenwyk J, Siegel P, Njai R. Housing Insecurity and the Association with Health Outcomes and Unhealthy Behaviors, Washington State, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:140511.

[3] Maqbool N, Viveiros J, Ault M. The Impacts of Affordable Housing on Health: A Research Summary. Center for Housing Policy Insights from Housing Policy Research. 2015.

[4] Aidala, AA, Lee G, Abramson DM, et al. Housing Need, Housing Assistance, and Connection to HIV Medical Care. AIDS Behav 2007;11(2).

[5] Schaeffer K. Key facts about housing affordability in the U.S. Pew Research Center 2022.

[6] Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. The State of the Nation’s Housing 2022. Harvard University 2022.

[7] Christensen P, Sarmiento-Barbieri I, Timmins C. Racial discrimination and housing outcomes in the United States rental market. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper. 2021.

[8] Operario D, Nemoto T. HIV in Transgender Communities: Syndemic Dynamics and a Need for Multicomponent Interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55(Suppl 2):S91-3.

[9] Frederick TJ, Chwalek M, Hughes J, Karabanow J, Kidd S. How stable is stable? Defining and measuring housing stability. Journal of Community Psychology 2014;42(8):964–79.

[10] CDC. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons with diagnosed HIV infection—Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2018 Cycle (June 2018–May 2019). HIV Surveillance Special Report 25;2020.

[11] Bucholtz S. Message from PD&R Senior Leadership: Measuring Housing Insecurity in the American Housing Survey. PD&R Edge 2018.

[12] The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act 2011 as amended by S. 896 The Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act of 2009.

[13] Bailey KT, Cook JT, Ettinger de Cuba S, et al. Development of an index of subsidized housing availability and its relationship to housing insecurity. Housing Policy Debate 2016;26(1):172–87.

[14] Aidala A, Cross JE, Stall R, Harre D, Sumartojo E. Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: implications for prevention and policy. AIDS Behav 2005;9(3):251-65.

[15] Berthaud V, Johnson L, Jennings R, et al. The effect of homelessness on viral suppression in an underserved metropolitan area of middle Tennessee: potential implications for ending the HIV epidemic. BMC Infectious Diseases 2022;22(144).

[16] Wolitski RJ, Kidder DP, Fenton KA. HIV, Homelessness, and Public Health: Critical Issues and a Call for Increased Action. AIDS Behav 2007; 11(2):167.

[17] Wainwright JJ, Beer L, Tie Y, et al. Socioeconomic, Behavioral, and Clinical Characteristics of Persons Living with HIV Who Experience Homelessness in the United States, 2015–2016. AIDS Behav 2020;24:1701-8.

[18] Arum C, Fraser H, Artenie AA, et al. Homelessness, unstable housing, and risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health 2021;6(5);e309-23.

[19] Doran KM, Fockele CA, Maguire M. Overdose and Homelessness—Why We Need to Talk About Housing. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(1):e2142685.

[20] CDC. Behavioral and Clinical Characteristics of Persons with Diagnosed HIV Infection—Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2020 Cycle (June 2020–May 2021). HIV Surveillance Special Report 2020;29.

[21] Padilla M et al. Mental health, substance use and HIV risk behaviors among HIV-positive adults who experienced homelessness in the United States – Medical Monitoring Project, 2009–2015. AIDS Care 2020;5.

[22] Pichon LC, Rossi KR, Chapple-McGruder, et al. A Pilot Outreach HIV Testing Project Among Homeless Adults. Front Public Health 2021;9:703659.

[23] Morrell KR, Pichon LC, Chapple-McGruder T, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of HIV-Risk Behaviors among Homeless Adults in a Southern City. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice 2014;7(1).

[24] Nelson KM, Thiede H, Hawes SE, et al. Why the wait? Delayed HIV diagnosis among men who have sex with men. J Urban Health 2010;87(4):642-55 in HUD. HIV Care Continuum: The Connection Between Housing and Improved Outcomes Along the HIV Care Continuum.

[25] Desai MM, Rosenheck RA. HIV Testing and Receipt of Test Results Among Homeless Persons With Serious Mental Illness. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:2287-94.

[26] Wenzel SL, Rhoades H, Tucker JS, et al. HIV risk behavior and access to services: what predicts HIV testing among heterosexually active homeless men? AIDS Educ Prev 2012;24(3):270-9.

[27] McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet;2016;387(10013):53-60.

[28] Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(1):75-84.

[29] Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(10):1601-3.

[30] Santa Maria D, Flash CA, Narendorf S, et al. Knowledge and Attitudes About Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Young Adults Experiencing Homelessness in Seven U.S. Cities. Journal of Adolescent Health 2019;64(5):574-80.

[31] Harris RA, Xue X, Selwyn PA. Housing Stability and Medication Adherence among HIV-Positive Individuals in Antiretroviral Therapy: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74(3):309-17.

[32] Creasy SL, Henderson ER, Bukowski LA, et al. HIV Testing and ART Adherence Among Unstably Housed Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States. AIDS Behav 2019;23(11):3044-51.

[33] Palepu A, et al. Homelessness and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy among a Cohort of HIV-Infected Injection Drug Users. Journal of Urban Health 2011;88:545-55.

[34] Riley ED, Vittinghoff E, Koss CA, et al. Housing first: unsuppressed viral load among women living with HIV in San Francisco. AIDS Behav 2020;23(9):2326-36.

[35] Rajabiun S, Tryon J, Feaster M, et al. The Influence of Housing Status on the HIV Continuum of Care: Results From a Multisite Study of Patient Navigation Models to Build a Medical Home for People Living With HIV Experiencing Homelessness. AJPH 2018;108:S539-45.

[36] HUD. The 2021 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Sheltered Homelessness. 2022.

[37] CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the Untied States and dependent areas, 2020. HIV Surveillance Report 2021;33.

[38] U.S. Census Bureau. Population Estimates, July 1 2021 (V2021) – United States. Quick Facts. Accessed October 21, 2022.

[39] Ibragimov U, Beane S, Adimora AA, et al. Relationship of racial residential segregation to newly diagnosed cases of HIV among black heterosexuals in US metropolitan areas, 2008–2015. J Urban Health 2019;96:856–67.

[40] Dailey AF, Gant Z, Hu X, et al. Association Between Social Vulnerability and Rates of HIV Diagnoses Among Black Adults, by Selected Characteristics and Region of Residence — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:167-70.

[41] U.S. Census Bureau. Population Estimates, July 1 2021 (V2021) – United States. Quick Facts. Accessed October 21, 2022.

[42] Fusaro VA, Levy HG, Shaefer HL. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Lifetime Prevalence of Homelessness in the United States. Demography 2018;55(6):2119-28.

[43] Young SD, Rice E. Online social networking technologies, HIV knowledge, and sexual risk and testing behaviors among homeless youth. AIDS Behav 2011;15(2):253-60.

[44] Call J, Gerke D, Barman-Adhikari A. Facilitators and barriers to PrEP use among straight and LGB young adults experiencing homelessness. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 2022;34(3);285-301.

[45] CDC. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2019. HIV Surveillance Report 2019;32.

[46] Myles RL, Best J, Bautista G, et al. Factors Associated with HIV Testing Among Atlanta’s Homeless Youth. AIDS Educ Prev 2020;32(4):325-36.

[47] Logan JL, Frye A, P HO, et al. Correlates of HIV Risk Behaviors Among Homeless and Unstably Housed Young Adults. Public Health Rep 2013;128(3):153-60.

[48] Henwood BF, Rhoades H, Redline B, et al. Risk behaviour and access to HIV/AIDS prevention services among formerly homeless young adults living in housing programs. AIDS Care 2020;32(11):1457-61.

[49] Homelessness Research Institute. Transgender Homeless Adults & Unsheltered Homelessness: What the Data Tell Us. National Alliance to End Homelessness. 2020.

[50] Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, et al. Estimating the Prevalence of HIV and Sexual Behaviors Among the US Transgender Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, 2006-2017. Am J Public Health 2019;109(1):e1-e8.

[51] Adimora AA, Auerback JD. Structural Interventions for HIV Prevention in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;55:S132-5.

[52] Lee CT, Winquist A, Wiewel EW, et al. Long-Term Supportive Housing is Associated with Decreased Risk for New HIV Diagnoses Among a Large Cohort of Homeless Persons in New York City. AIDS Behav 2018;22(9):3083-90.

[53] Wolitski RJ, Kidder DP, Pals SL, et al. Randomized Trial of the Effects of Housing Assistance on the Health and Risk Behaviors of Homeless and Unstably Housed People Living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2010;14:493-503.

[54] Biello KB, Bazzi AR, Vahey S, et al. Delivering Preexposure Prophylaxis to People Who Use Drugs and Experience Homelessness, Boston, MA, 2018–2020. AJPH 2021;111:1045-8.

[55] Jacob V, Chattopadhyay SK, Attipoe-Dorcoo S, et al. Permanent Supportive Housing With Housing First: Findings From a Community Guide Systematic Economic Review. Am J Prev Med 2022;62(3):e188-201.

[56] Holtgrave DR, Wolitski RJ, Pals SL, et al. Cost-utility analysis of the housing and health intervention for homeless and unstably housed persons living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2013;17(5):1626-31.

[57] Holtgrave DR, Briddell K, Little E, et al. Cost and threshold analysis of housing as an HIV prevention intervention. AIDS Behav 2007;11:S162-6.

[58] The White House. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States 2022-2025. Washington, DC 2021.

[59] Griffin A, Dempsey A, Cousino W, et al. Addressing disparities in the health of persons with HIV attributable to unstable housing in the United States: The role of the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. PLoS Med 2020;17(3):e1003057.

[60] Pitchford P. City of Riverside Receives $10 Million State Grant to assist with Project Legacy. City of Riverside Press Release. 2021 Nov.

[61] Hickey MD, Imbert E, Appa A, et al. HIV treatment outcomes in POP-UP: drop-in HIV primary care model for people experiencing homelessness. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022.

[62] Lysander K, Perloff J. Chicago House Performance Report Card FY2021.

[63] Bazzi AR, Shaw LC, Biello KB, Vahey S, Brody JK. Patient and Provider Perspectives on a Novel, Low-Threshold HIV PrEP Program for People Who Inject Drugs Experiencing Homelessness. J Gen Intern Med 2022;1-9.

[64] Lightner JS, Barnhart T, Shank J, et al. Outcomes of the KC life 360 intervention: Improving employment and housing for persons living with HIV. PLoS One 2022.

[65] Housing and Employment Success Stories: Innovative System Service Delivery Supporting the HIV Care Continuum. City of Kansas City, MO Health Department. 2020 National Ryan White Conference on HIV Care & Treatment.

CDC will continue working with partners within and across agencies and communities to garner support for housing-related interventions as an effective HIV prevention strategy and ensure people can access the health and social services they need to stay healthy.

Healthcare, community-based, and other service providers can meet people where they are with integrated HIV and other health and social services, including outside of traditional clinical settings, such as through telehealth, mobile units, STI clinics, syringe services programs (SSPs), and shelters. They can also implement integrated models of care that link people to the health and social services they need, including through patient navigator programs. They can also provide HIV prevention education specific to populations experiencing housing instability.

Community leaders can work to build federal, state, and local support for integrated service models for people with HIV and people who could benefit from HIV prevention. For example, they can speak about the benefits of integrating health and social services, like housing support, to address comprehensive, whole-person needs. They can also speak about the importance of staying engaged in ongoing HIV and other care.